Polish version

Stop: Literature

Meet a few of the greatest Cracow writers at the bus stop!

But if you are already here, you might as well check free books and eight short literary works of leading Cracow writers available outside the Woblink application:

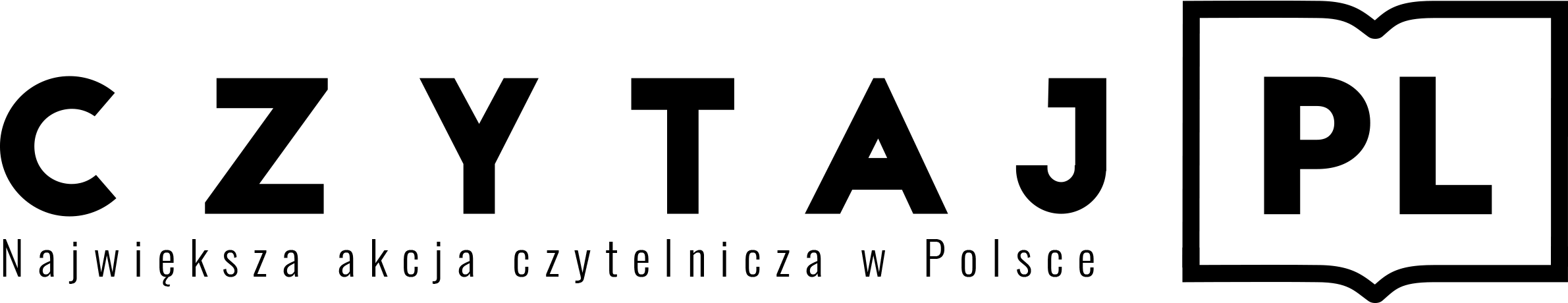

Joseph Conrad

(1857–1924) one of the greatest writers in the history of world literature. Born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, he was a son of Apollon, a poet, eminent independence activist, a prisoner of Tsarist Russia and deportee. In his childhood, after the death of his mother, Joseph Conrad lived in Krakow for five years beginning on 20th February 1869. In May the same year his father died.. At the age of 17, in October 1874, he left for France, where he became a sailor and later moved to the British navy. In 1894, he settled down in England and devoted himself to writing: within a year he had published his first novel. Many of his novels entered the classical canon of world literature, with the most famous being Heart of Darkness.

Joseph Conrad returned to Poland only once, already a mature man: on 28th July 1914, together with his wife Jessie, and sons Borys and John accompanied by Józef and Otolia Retinger, intending to stay at Otolia’s mother’s home in Goszcza. His memories, taken down in 1921, contain traces of the places he visited: the Jagiellonian Library and the estate of Konstanty Buszczyński in Górka Narodowa. He left the city for Zakopane by rail. (ezp)

Read the „Notes on life and letters” by Joseph Conrad.

Listen the „Notes on life and letters” by Joseph Conrad (read by Piotr Czarnota, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

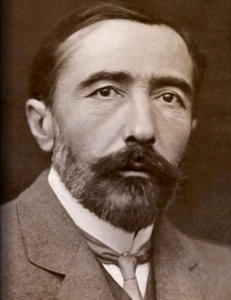

Stanisław Lem

Stanisław Lem

(1921–2006) It is hard to imagine a Krakow that has never been home to Stanisław Lem, one of the greatest science-fiction writers, philosopher, journalist, and essayist. His works – extensive, varied, and unfathomed at a cosmic scale – have won over fans from all over the world. The writer was, however, born in Lviv, which remained his beloved city throughout his life. Krakow – where he made his home after repatriation – remains practically absent from Lem’s main current of work. In 1946, having left Lviv, he moved in with his parents in a flat on Śląska Street. At the time, Stanisław was already a student at the Medical Department of the Jagiellonian University, yet as he had already been publishing his works for many months, he never graduated (1948), a decision that determined the future career path for this man of letters. His further addresses were 22 Krupnicza Street (the famous Writers’ House) and a tenement house on Bonerowska Street – the first place he lived together with his wife Barbara. They later moved to Kliny district in the 1950s. There, a newly built house on Narwik Street was their home until the 1980s when Lem built a new house in the same street, where he lived until his death. On 4th April 2006, Stanisław Lem was buried at Salwatorski cemetery in Krakow. (ezp)

Read one of the „The Tales of the Robots” by Stanisław Lem (translated by Michael Kandel).

Listen one of the „The Tales of the Robots” by Stanisław Lem (read by Marta Meissner, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

Stanisław Wyspiański

Stanisław Wyspiański

One of the most eminent and certainly the most versatile Polish artist of all times, connected to Krakow in his entire lifetime. In the city, he perceived the vastness of tradition and the dramatic quality of his contemporary times. He was a genius of an artist, as manifested especially in the multi-directional quality of his pursuits: a consummate poet, a dramatist, and theatre producer; equally talented as a painter, draughtsman, and designer (of stained-glass decorations, polychrome murals, furniture, stage sets, and costumes). One of the founders of the Polish tradition, a permanent point of reference for successive generations of artists. The house where Stanisław Wyspiański was born on 15th January 1869 stands at 26 Krupnicza Street, and today houses the Museum of Józef Mehoffer. The artist’s studio was situated at 9 Mariacki Square, where a range of dramas were written after 1898, notably Lelewel, Klątwa (The Curse), Legion, and the beginning of Wesele (The Wedding). In turn, the famous “blue studio” at 79 Krowoderska Street, where Wyspiański came to live after his marriage in September 1900, was his home whilst he completed Wesele, Wyzwolenie (Liberation), Bolesław Śmiały (Boleslaus the Bold), Akropolis, and Noc listopadową (November Night). The artist’s remains lie in the “Polish National Pantheon” Crypt of the Church “on the Rock” (na Skałce). (ezp)

Read the „Oh, I adore Krakow” by Stanisław Wyspiański (translated by Joanna Bilmin).

Listen the „Oh, I adore Krakow” by Stanisław Wyspiański (read by Piotr Czarnota, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

Tadeusz Peiper

Tadeusz Peiper

(1891–1969) One of the most important artists of the Polish avant-garde, he coined the “three Ms” strain in poetry (Metropolis, Mass, Machine; Polish: miasto, masa, maszyna) in the inter-war period. Founder and editor of Zwrotnica magazine, and an eminent animator of literary life before the Second World War. Brought up in an established Podgórze family, where his father (d. 1903) became the city’s deputy mayor. After a long time spent abroad, Peiper became actively involved with the avant-garde and was a regular of the avant-garde Esplanada café on the corner of Krupnicza and Podwale streets. He lived in a townhouse on ul. Jagiellońska, where he edited Zwrotnica. Peiper spent the war in the USSR (evacuated to Lviv, imprisoned by the NKVD, deported to the wastelands of Russia, he returned in 1944). After 1945 he lived in Lublin, Łódź, and shortly in Krakow – like many other writers, he turned to the undamaged Krakow to look for a place to live, and took lodgings in Writers’ House at 22 Krupnicza Street. Shortly afterwards he left to settle permanently in Warsaw. (ezp)

Read the „Flower of the street” by Taduesz Peiper (translated by Katarzyna Badura).

Listen the „Flower of the street” by Taduesz Peiper (read by Piotr Czarnota, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

Julian Przyboś

Julian Przyboś

(1901–1970) A poet, essay writer, editor of literary magazines. His biography portrays the level of complexity of the lives of Polish artists in the 20th century. A youth fighting with the Ukrainians for Lviv, and later with the Bolsheviks in 1920; in the inter-war period he was one of the originators of the Krakow avant-garde and a teacher. After the capture of Lviv by the Soviets, he collaborated with the Russian occupiers. He found himself in Krakow in 1920, enrolled in the Faculty of Polish Studies of the Jagiellonian University. During this time he also cooperated with Tadeusz Peiper and his Zwrotnica magazine. After the war, following a diplomatic episode (he was a delegate of the People’s Republic of Poland to Switzerland in 1947–1951), Przyboś held the post of Director of the Jagiellonian Library. Rumoured to be bored to death there, he used to spend plenty of time at the nearby headquarters of Przekrój weekly (today’s 19 Piłsudskiego Street). He finished his career as a librarian in 1955 and moved to Warsaw. (ezp)

Read the „Trace” by Julian Przyboś (translated by Gabriela Łagowska).

Listen the „Trace” by Julian Przyboś (read by Piotr Czarnota, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

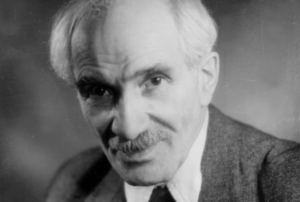

Adam Ważyk

Adam Ważyk

(1905-1982) poet, prose writer, essayist.

In the 1920s, he was connected with the Krakow avant-garde and co-edited the Almanach Nowej Sztuki magazine. He published then two collections of poems: Semafory and Oczy i usta. Before the outbreak of World War II he published a novel Mity rodzinne.

During the War, he was connected with the Soviet authorities, as well as with Polish Armed Forces in the USSR, for the 1. Corps of which he wrote the leading March. After the end of the War, he cooperated with numerous cultural magazines, including Kuźnica and Nowa Kultura. He also held the post of the secretary of Związek Zawodowy Literatów Polskich (the Trade Union of Polish Men of Letters) and took active part in introducing social realism. In 1955, he decided – as one of the first Polish intellectuals – to settle with Stalinism. His Poemat dla dorosłych (A Poem for Adults) marks the end of the social realism era in Poland. In 1957, he left the Polish United Workers’ Party to signal his protest against stopping the publication of the Europa magazine, which he co-edited. In 1964, he signed the “Letter of the 34” concerning the protection of the freedom of speech. He engaged himself also in the defence of students expelled from the University of Warsaw in 1968.

Ważyk was also a translator, mainly of French poetry. He translated poems by Apollinaire, Aragon, Cendrars and Jacob, contributing to the familiarising of the Polish language with the achievements of French literary avant-garde. (mj)

Read „A poem for adults” by Adam Ważyk (translated by Irina Livezeanu).

Listen „A poem for adults” by Adam Ważyk (read by Piotr Czarnota, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

Bruno Jasieński

Bruno Jasieński

(born in Kilmontów in 1901, died in Moscow in 1938), co-initiator of Polish futurism, a poet and communist activist, murdered in Moscow by the Stalinist regime. A son to a Jewish doctor, while his mother was of nobility descent, he was born Wiktor Zysman (later he was adopted by the Jasieński family but his biological parents still took care of him). He spent early childhood in his native Klimontów, then went to primary school in Warsaw. During the First World War he was in Moscow. Having returned to Poland in 1919, he began his studies in Krakow – initially in philosophy, then in law. Four years later he was already active in Lviv where he joined the artistic avant-garde. In the aftermath of the events which took place in Krakow in 1923, when 18 workers participating in a demonstration were killed and a couple of dozens injured in the fighting with the police and the army, Jasieński became a communist. His political choice led him to complete identification with the Soviet Union (after a stay in Paris, he settled in the USSR in 1929). However, this did not save him from Stalin’s great purge in the 1930s. In 1937 he was arrested in Moscow, sentenced to death and executed on the same day.

In Krakow, Bruno (the name he took in 1920) Jasieński, rejected by the Skamandryci group, in 1920 organised the first poetry soirée (poezowieczór) of the Futurist Club “Pod Katarynką” [Hurdy-Gurdy], held at the Esplanada café in Krupnicza Street (at the intersection with Podwale Street). Among the Club members were Stanisław Młodożeniec, a student and poet, and the painter and writer Tytus Czyżewski, who was already well known in the artistic milieu. Shortly after that Jasieński had his debut in the Krakow-based Formiści periodical under chief editor Czyżewski. While in Krakow, Bruno Jasiński lived in a student hostel at Jabłonowskich Street; his other Krakow addresses were Na Groblach Square and Radziwiłłowska Street.

Read „The City” by Bruno Jasieński (translated by Dominika Stankiewicz).

Listen „The City” by Bruno Jasieński (read by Wojciech Barczyński, recorded by Radiofonia Association):

Jalu Kurek

Jalu Kurek

(1904–1983) – a poet and prose writer strongly connected to the circles of Krakow Avant-garde. Best known for his two novels: Grypa szaleje w Naprawie (Influenza ravages Naprawa, 1934) and Woda wyżej (High Water, 1935). A major share of his works were devoted to Krakow and the mountains, and especially to the Tatras he was in love with. Famous for an extraordinary sense of humour. During the promotion of one of his volumes, he advertised it with the following rowdy epigram, making fun of his own name (Kurek – tap). The park bearing his name is situated in Krakow’s Szlak Street. (ms)

Read „Cracow 422” by Jalu Kurek (translated by Magda Zeman).

Listen „Cracow 422” by Jalu Kurek (read by Marta Meissner, recorded by Radiofonia Association):